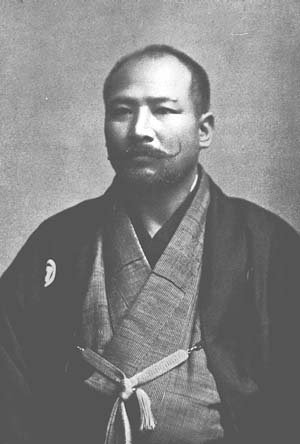

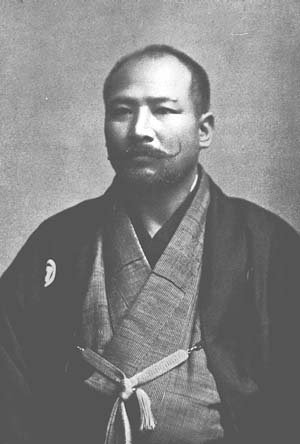

The following quote was recorded by the early Western judoka E. J. Harrison in his book The Fighting Spirit of Japan (1913). It is an account from a fellow judoka, Sakujiro Yokoyama (pictured above) of a samurai duel that he witnessed as a child in Japan.

"I can carry my memory back to the days when all samurai wore the two swords and used them as well when necessity arose. When quite a boy I accidentally witnessed an exciting duel to the death between a ronin [an unattached samurai] and three samurai. The struggle took place in the Kojimachi ward, in the neighbourhood of Kudan, where the Shokonsha now stands.

Before proceeding with my narrative, I ought to explain for the benefit of my foreign listeners [there were two of us present besides another Japanese gentleman] the usage that was commonly observed by the two-sworded men of the old feudal days, in order that the incident I am about to describe may be better understood.

The sword of the samurai, as you know, was a possession valued higher than life itself, and if you touched a samurai's sword you touched his dignity. It was deemed an act of unpardonable rudeness in those days for one samurai to allow the tip of his scabbard to come into contact with the scabbard of another samurai as the men passed each other in the street; such an act was styled saya-ate {saya = scabbard, ate = to strike against}, and in the absence of a prompt apology from the offender a fight almost always ensued.

The samurai carried two swords, the long and the short, which were thrust into the obi, or sash, on the left-hand side, in such a manner that the sheath of the longer weapon stuck out behind the owner's back. This being the case, it frequently happened, especially in a crowd, that two scabbards would touch each other without deliberate intent on either side, although samurai who were not looking for trouble of this kind always took the precaution to hold the swords with the point downward and as close to their sides as possible.

But should a collision of this description occur, the parties could on no account allow it to pass unnoticed. One or both would at once demand satisfaction, and the challenge was rarely refused. The high sense of honour which prevailed among men of this class forbade them to shrink from the consequences of such an encounter. So much by way of introduction. The episode I am going to describe arose in precisely this fashion.

The parties to the duel were a ronin and three samurai, as I have already said. The ronin was rather shabbily dressed and was evidently very poor. The sheath of his long sword was covered with cracks where the lacquer had been worn away through long use. He was a man of middle age. The three samurai were all stalwart men and appeared to be under the influence of sake.

They were the challengers.

At first the ronin apologized, but the samurai insisted on a duel, and the ronin eventually accepted the challenge. By this time a large crowd had gathered, among which were many samurai, none of whom, however, ventured to interfere. In accordance with custom, the combatants exchanged names and swords were unsheathed, the three samurai on one side facing their solitary opponent, with whom the sympathies of the onlookers evidently lay.

The keen blades of the duellists glittered in the sun. The ronin, seemingly as calm as though engaged merely in a friendly fencing bout, advanced steadily with the point of his weapon directed against the samurai in the centre of the trio, and apparently indifferent to an attack on either flank. The samurai in the middle gave ground inch by inch and the ronin as surely stepped forward.

Then the right-hand samurai, who thought he saw an opening, rushed to the attack, but the ronin, who had clearly anticipated this move, parried and with lightning rapidity cut his enemy down with a mortal blow. The left-hand samurai came on in his turn, but was treated in similar fashion, a single stroke felling him' to the ground bathed in blood. All this took almost less time than it takes to tell.

The samurai in the centre, seeing the fate of his comrades, thought better of his first intention and took to his heels. The victorious ronin wiped his blood-stained sword in the coolest manner imaginable and returned it to its sheath. His feat was loudly applauded by the other samurai who had witnessed it. The ronin then repaired to the neighbouring magistrate's office to report the occurrence, as the law required."