The History of the Roman Army

The Roman Army

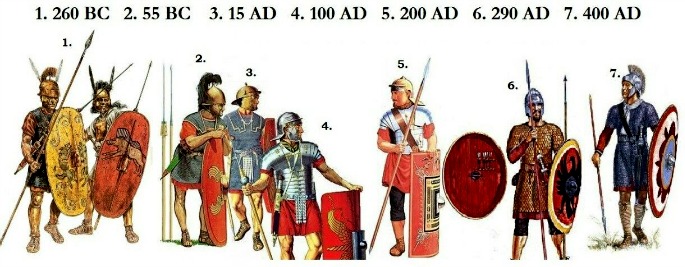

The Roman army of the ancient world covers the period from around the seventh century BCE to around the fifth century CE.

At the height of the army’s power (from around the end of the second century BCE to the second century CE), they were highly trained professional soldiers who were so skilled in

battle, that they were able to conquer much of the known world.

Talk the Talk

Throughout the Roman Period, the army faced many different

types of opponents which gave them great versatility on the battlefield.

They adapted the best tactics, armour and weapons they came across and absorbed them into their own

army, both by applying them to the legionaries and by adding auxiliary troops from the conquered nations to their armed forces.

This ability to adapt and evolve helped them grow in strength and led to them becoming the most powerful force on earth for hundreds of years.

The history of the Roman army can be loosely divided into three eras:

The history of the Roman army can be loosely divided into three eras: The first is the civilian militia army from the Period of Kings to the early Roman Republic (from around the seventh century to the first century BCE), which helped take Rome from being a small city-state to the most powerful force in Italy.

The second was the professional army that helped elevate Rome into the great empire it would become and the third was the army of the later period that would ultimately see the collapse of the Roman Empire.

The Early Roman Army

In the seventh century BCE, Rome was a city-state much like many others in what is now Italy. They had no standing army, but instead were defended when needed by a militia made up of able-bodied male citizens who would go back to their normal professions, usually farmers and herders, after the troubles had subsided. They would supply their own weapons, armour and anything else they required for war meaning the wealthier the soldier, the better equipped for battle he was.

The Roman army is believed to have progressed in the sixth century BCE when King Servius Tullius organised the troops into five classes of soldiers split into units of standardised sizes that were separated by wealth and the level of equipment they could afford. The reforms of Tullius also probably led to the adoption of the fighting tactics of the Etruscans and Greek colonists in Southern Italy who were rivals to the Romans. Known as hoplite tactics, they fought by forming groups known as phalanxes that went into battle in tight formations equipped with shields, spears and bronze and leather body armour that covered the front and back of their torsos.

By the third century BCE, this had evolved into legions which consisted of thirty units known as manipulus (literally a handful), each of which contained between sixty to one-hundred and twenty men.

Most of the soldiers would by this time be armed with a short stabbing sword known as a gladius, a pilum which was a long spear or javelin made for hand-to-hand combat as well as throwing at an enemy and most soldiers were protected by an oval shield.

On the battlefield, the maniples were organised into three battle lines which allowed for more flexibility than the ridged phalanxes formations. Each line would consist of around ten manipulus, with the younger soldiers known as hastati at the front, the second line consisting of hardened soldiers known as principes usually drawn from the Roman middle classes and the third line was made up of the triarii, a group of battle-hardened veterans who were usually the wealthier of the three groups and therefore the best equipped.

Cavalry units known as equites would help protect the flanks of the infantry on the battlefield and a skirmishing unit known as the velites would also support the main force. However, by the second century BCE, the velites were disbanded and the cavalry would usually be made up of auxiliary troops from conquered nations who had gained some level of citizenship.

The Golden Age of Rome

In the second century BCE Rome had a series of wars with Carthage. This included fifteen years of fighting against Hannibal and his troops and culminated in the Third Punic War in 146 BCE that led to the destruction of Hannibal's homeland. Despite their ultimate emphatic victory, it was realised over the coming decades that the civilian militia army was not strong enough so a series of reforms, led by Gaius Marius, instigated the forming of a professional army.

The soldiers would now have their equipment provided for them by the state and were expected to serve for twenty-five years once they signed up. This meant they would gain more training, experience and expertise in executing battle tactics which led to them becoming the most formidable force on the planet.

They were not allowed to marry while enlisted and on retirement, would be given a pension or a plot of land to farm.

Many soldiers would continue to serve beyond the twenty-five-year tour of duty, though this was not always out of choice. If injured and unable to continue his career in the military, a

legionary would be given a medical discharge (missio causaria) or an honourable discharge (honesta mission). On leaving the

army, these men would have a high social status and would be exempt from paying taxes and other civic

duties.

The Roman army was made up of men

over the age of twenty who were classed as Roman citizens. However, through this period an increasing number of legionaries would be made up of non-Italians who had gained citizenship,

usually coming from nations that had previously been conquered such as Spain, Gaul (France) Britain and North Africa.

The army was organised into legions, usually about thirty at

any given time which consisted of around five thousand soldiers known as legionaries and was commanded by a legate. A legion would consist of ten cohorts, each of which was divided into six

centuries consisting of around eighty legionaries that were led by a centurion.

Some soldiers would have specialist skills such as archery or the use of the slingshot, and others would be employed as artillerymen, who fired huge catapults known as onagers or large wind-up crossbows called ballistas. However, most Roman soldiers would usually fight on foot as infantrymen though they would be supported by cavalry troops who would often chase down any fleeing enemy combatants when the battle was won. The army would also employ auxiliary troops that were made up of soldiers who were not Roman citizens. Their pay would be around a third of what the legionaries would be compensated, and they would often be expected to fight on the front battle lines where the fighting was the most dangerous.

The armour worn by a legionary soldier in this period was known as lorica segmentata and was made from strips of iron and leather. His helmet, known as a galea was made of metal that included neck and cheek protection and on his feet, he wore leather sandals that had iron studs on the bottom to make them hard wearing during long marches.

He went into battle with a rectangular shield made of wood and leather known as a scutum that curved back around the soldier which allowed a legion to form an almost impenetrable wall when attacked. They usually marched into battle with their shields facing the opposing force, so they were always ready to defend themselves.

Even when attacked from above with rocks or arrows, they could protect themselves by forming the testudo (Latin for tortoise), whereby they would raise their shields over their heads with the men at the front forming a frontal barrier, those at the back protecting the rear and those on the sides holding their shields to protect that area, forming a shell-like cover that looked much like, as the name suggests, a tortoise.

The legionary’s main weapon in close quarters was still the gladius which allowed for short under-arm thrusts in melee. He would also still carry a pilum which by this time had a sharp point made of iron, with a thin and bendable shaft which made it difficult to remove when it lodged in an enemy’s shield, often meaning he would need to discard it making him vulnerable to further attacks.

The Later Roman Period

As time went on and the empire grew, more and more of the army was made up of people from the colonies and the line between the auxiliary units and the professional legionaries became blurred. There was a growing number of mounted archers employed in the Roman forces and the cavalry seems to have become more important to their battle tactics, though to what extent is debated by historians.

The standards of training and expertise required to be classed as a Roman soldier diminished over time and by the end of the period, some argue that they fought much like warriors of the early medieval period that would follow with a lot less organisation, especially in larger battles. The gladius was largely replaced with spatha swords which had longer blades, the shields they carried were now round and segmented armour also largely fell out of use.

As well as field units known as comitatensis who fought in battle, there was a growing number of garrison troops called limitanei who were usually stationed on the borders of Roman territory.

As the political climate of Rome changed so did the army, in some ways for the better, and in others for the worse. By the end of the period, their forces had become convoluted and overstretched due to the sheer size of the territory that needed defending and a lack of political solidarity within the empire. This would lead to divided loyalties and would ultimately see the downfall of the Roman Empire.

Written by Andrew Griffiths – Last updated 24/08/2023. If you like

what you see, consider following the History of Fighting on social media.

Further Reading:

Andrew Knighton. [Internet]. 2016. 3 Key Phases in the History of the Roman Army. War History Online. Available From: https://www.warhistoryonline.com/featured/3-key-phases-in-the-history-of-the-roman-army.html [Accessed Sept 06, 2018].

Dattatreya Mandal. [Internet]. 2017. Evolution of the Ancient Roman Soldier. Realm of History. Available From: https://www.realmofhistory.com/2017/07/13/evolution-ancient-roman-soldier [Accessed Sept 06, 2018].

Roman Weapons and Armor. [Internet]. 2018. Penn State University. Available From: http://sites.psu.edu/grandromanstrategy/2014/04/03/roman-weapons-and-armor [Accessed Sept 06, 2018].

The Roman Army. [Internet]. 2016. History on the Net. Available From:

https://www.historyonthenet.com/the-romans-the-roman-army [Accessed Sept 06, 2018].

What Was Life Like in the Roman Army? [Internet]. 2018. BBC. Available From: http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/romans/the_roman_army [Accessed Sept 06, 2018].

More Roman History

The Period of Kings in Ancient Rome

A look at the early history of ancient Rome, commonly known as the Period of Kings. While much of this period in Rome’s history is steeped in myth and legend, it is clear that it began to expand soon after its conception. Its population and territories grew under a series of kings who worked in tandem with an elected senate.

The Roman Republic

The Roman Republic era spanned nearly five hundred years from around 509 – 31 BCE and was a time of great expansion and innovation. The foundation of Roman law was laid, infrastructure was greatly improved, the Roman army went from being a local militia to one of the most formidable professional armies the world had ever seen and the territories of ancient Rome grew exponentially.

The Roman Republic era spanned nearly five hundred years from around 509 – 31 BCE and was a time of great expansion and innovation. The foundation of Roman law was laid, infrastructure was greatly improved, the Roman army went from being a local militia to one of the most formidable professional armies the world had ever seen and the territories of ancient Rome grew exponentially.

The images on this site are believed to be in the public domain, however, if any mistakes have been made and your copyright or intellectual rights have been breeched, please contact andrew@articlesonhistory.com.