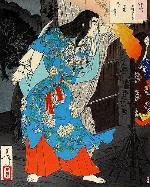

The Mongol Hordes vs. The Samurai Warriors

Talk the Talk

From around the beginning of the 13th century, the Shikken was the title for the Regent of the Shogun in Japan.

The holder of the title was the ipso-facto ruler of the country in charge of national defence, the treasury and matters of law.

The post was monopolised by the Hojo Clan right up until the fall of the Kamakura shogunate in 1333 and made both the Shogun and the Emperor effectively ceremonial positions.

The holder of the title was the ipso-facto ruler of the country in charge of national defence, the treasury and matters of law.

The post was monopolised by the Hojo Clan right up until the fall of the Kamakura shogunate in 1333 and made both the Shogun and the Emperor effectively ceremonial positions.

Walk the Walk

To gain a foothold in Southern China, Kublai Khan was engaged in a siege that took nearly six years to complete.

The Battle of Xiangyang went on from 1267 – 1273 and was important due to its strategically vital position next to the Han River.

The walls of Xiangyang City were virtually impenetrable which is why the stalemate lasted so long. Undeterred, Kublai Khan summoned two Persian engineers to build him catapults, something he had heard of but never seen.

Their effects were instantly devastating and allowed the Mongols to begin a process of conquering the whole of China, which was previously considered unthinkable as China was considered to be the height of civilisation while the Mongols were seen as barbarians.

The Battle of Xiangyang went on from 1267 – 1273 and was important due to its strategically vital position next to the Han River.

The walls of Xiangyang City were virtually impenetrable which is why the stalemate lasted so long. Undeterred, Kublai Khan summoned two Persian engineers to build him catapults, something he had heard of but never seen.

Their effects were instantly devastating and allowed the Mongols to begin a process of conquering the whole of China, which was previously considered unthinkable as China was considered to be the height of civilisation while the Mongols were seen as barbarians.

Samurai Quote

"Other than advancing and having my deeds known, I have nothing else to live for".

~ Takezaki Suenaga after the invasion of the Mongol Hordes ~

~ Takezaki Suenaga after the invasion of the Mongol Hordes ~

The famous Mongol Hordes were probably the most powerful force on earth by the mid-thirteenth century with a vast empire that stretched from the Danube to the Sea of Japan and from Northern Siberia to Cambodia.

The famous Mongol Hordes were probably the most powerful force on earth by the mid-thirteenth century with a vast empire that stretched from the Danube to the Sea of Japan and from Northern Siberia to Cambodia. It covered a landmass of an estimated thirty-three million square km which equates to 22% of the Earth's total land area and held sway over a population of over a hundred million people. In contrast, Kamakura Period Japan was a small island that was divided by internal conflict with rival warlords fighting amongst themselves for land, privileges and resources.

The Imminent Invasion of the Mongol Hordes

In 1268 the Mongol leader, Kublai Kahn (the grandson of the nation’s founder Genghis) sent his emissaries to Japan to demand acknowledgment of Mongol overlordship. This was denied by the Japanese but there was little immediate response to this defiance as the Kahn was engaged in conflict in China, in which he established a substantial foothold by 1273.A year later, he turned his attention back to Japan and sent an army made up of Mongol, Chinese and Korean soldiers out to conquer the insolent samurai warriors. The Mongols were a far more powerful army than their enemies in several ways including manpower, organisational skills and tactical awareness, something that the 18-year-old Shikken (Regent), Tokimune Hojo recognised. Even at that young age, he was an accomplished warrior and he realised how much danger the country was in so set about ending feuds between rival samurai clans in a bid to get them to unite against a common enemy.

The First Invasion of the Mongols

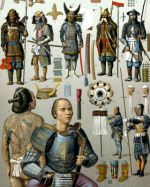

The first invasion came on November 19, 1274, when the Mongol Hordes landed at Hakata Bay and were met by Japanese warriors from the Kyushu Region. The samurai’s preferred style of combat by the thirteenth century was to charge into battle and challenge opposing warriors to individual combat during pitch battles. However, their foreign enemies used a different type of strategy.

They rode towards the samurai firing volleys of arrows laced with poison before retreating to stay out of range of their opponents. These waves of attacks continued relentlessly and were combined with the use of fire bombs that had probably been developed in China and burned not only the samurai warriors but also their mounts. The Japanese were forced to fall back into defensive formation but the Mongols could not build on their advantage and pursue any further due to a shortage of arrows.

They re-boarded their ships and left Hakata Bay with a decisive victory under their belts but as they did so, a storm came that destroyed a large part of their fleet with powerful winds, torrential rains and huge waves. They lost an estimated thirteen thousand men of a force that had been around thirty-five thousand strong at the start of the fighting and two hundred of their nine hundred ships were lost to the sea.

The Second Attack on Samurai Forces

For the next few years, Kublai concentrated on conquering Sothern China until in 1279, he sent more envoys to Japan demanding the leaders there pay homage to him. The reply was a resounding “no” and the messenger’s heads were returned to the Khan, minus their bodies. Kublai was furious but waited until May 1281 to attempt to exact his revenge.He raised an army of over two hundred thousand men and in preparation for the coming conflict, the Japanese constructed a wall 4.5 meters high and 40 km (25 miles) in length along the coast of Hakata Bay. They also assembled a large number of small boats that were designed specifically to fight in shallow waters in a bid to hamper their opponent’s ability to land troops.

The fleet was to attack in two waves, the first of which set out with nine hundred ships carrying forty thousand men which was to be followed by a further one hundred thousand soldiers and sixty thousand sailors who would be carried in three thousand, five hundred ships. The first wave reached Tsushima on the 9th of June and despite strong resistance, managed to overcome samurai forces there. They pushed on to Kyushu in Hakata Bay where the samurai managed to limit their ability to land troops to small numbers and employed night-time attacks on their ships.

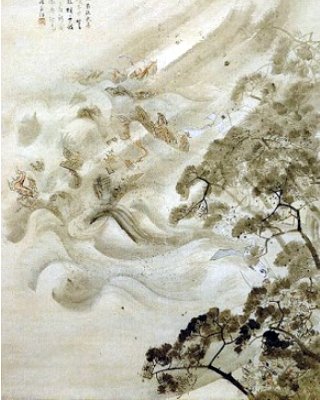

The Divine Wind

These tactics frustrated the Mongols who returned to their ships only to realise soon after doing so that they had made the same mistake again by invading Japan during typhoon season. Another storm hit with even greater ferocity than the last and devastated both the first and the second waves of the fleet. These winds, so it was believed by the Japanese, were evidence of intervention from the gods and became known as Kamikaze or the Divine Wind. Around four thousand Mongol ships were sunk and around one hundred thousand men lost their lives, forcing the fleet to return to China. Once again the Mongol Hordes had been defeated by natural forces which ended any major attempt for them to become the overlords of the samurai warriors.

Gracie, C. [Internet]. 2012. Kublai Khan: China's Favourite Barbarian. The BBC. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-19850234 [Accessed 10 May 2013].

Mongol Empire (1206 to 1368). [Internet]. 2013. Find the Data. Available from: http://empires.findthedata.org/l/2/Mongol-Empire [Accessed 10 May 2013].

Newman, J. 1989. Bushido – The Way of the Warrior. New York. Gallery Books.

Renius, A. [Internet]. 2009. The Mongols, the Samurai and the Divine Wind. Socyberty. Available from: http://socyberty.com/history/the-mongols-the-samurai-and-the-divine-wind [Accessed 10 May 2013].

Written by Andrew Griffiths – Last updated 22/10/2023. If you like

what you see, consider following the History of Fighting on social media.

Further Reading:

Cook, H. 1993. Samurai – The Story of a Warrior Tradition. London. Blandford Press.Gracie, C. [Internet]. 2012. Kublai Khan: China's Favourite Barbarian. The BBC. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-19850234 [Accessed 10 May 2013].

Mongol Empire (1206 to 1368). [Internet]. 2013. Find the Data. Available from: http://empires.findthedata.org/l/2/Mongol-Empire [Accessed 10 May 2013].

Newman, J. 1989. Bushido – The Way of the Warrior. New York. Gallery Books.

Renius, A. [Internet]. 2009. The Mongols, the Samurai and the Divine Wind. Socyberty. Available from: http://socyberty.com/history/the-mongols-the-samurai-and-the-divine-wind [Accessed 10 May 2013].

More Samurai History

Samurai History Home

A brief overview of the history of the samurai, looking at the rise and development of the leading social class in Japan and some of the cultural traits than made the samurai warriors unique.

A brief overview of the history of the samurai, looking at the rise and development of the leading social class in Japan and some of the cultural traits than made the samurai warriors unique.

The Heian

Period

The Heian Period was a time of major change in Japan as it saw the rise of a new warrior elite, the Samurai. The leaders of this new power would dominate the politics of the country for centuries and would even supplant the power of the Emperor, though not without a struggle.

The Heian Period was a time of major change in Japan as it saw the rise of a new warrior elite, the Samurai. The leaders of this new power would dominate the politics of the country for centuries and would even supplant the power of the Emperor, though not without a struggle.

Tomoe Gozen – Female Samurai Warrior

Tomoe Gozen is a rare example of a female Samurai warrior and is believed to have been involved in the Gempei wars (1180 – 1185). She fought alongside her Master, Minamoto Yoshinaka, though it is unclear how much of her story is actually true.

Tomoe Gozen is a rare example of a female Samurai warrior and is believed to have been involved in the Gempei wars (1180 – 1185). She fought alongside her Master, Minamoto Yoshinaka, though it is unclear how much of her story is actually true.

Yoshitsune Minamoto

The tragic tale of samurai legend Yoshitsune Minamoto. After helping his brother Yoritomo win the Genpei War and gain control of Japan, he was denied the titles and rewards he should have received for his services and was ultimately hunted down as a traitor.

The tragic tale of samurai legend Yoshitsune Minamoto. After helping his brother Yoritomo win the Genpei War and gain control of Japan, he was denied the titles and rewards he should have received for his services and was ultimately hunted down as a traitor.

The Kamakura Period

A look at the change and turmoil experienced by the ruling elite of Japan during the Kamakura Period and the Kemmu Restoration. A series of civil wars and two invasions from the Mongols saw powershifts not only between rival families, but also between the titles of the Emperor, the Shogun and the Regent.

A look at the change and turmoil experienced by the ruling elite of Japan during the Kamakura Period and the Kemmu Restoration. A series of civil wars and two invasions from the Mongols saw powershifts not only between rival families, but also between the titles of the Emperor, the Shogun and the Regent.

The Japanese Samurai Sword

The samurai sword, it is said, was believed to contain the soul of the warrior who owned it. While this is probably an over romanticised view, it is true to say that there was a spiritual connection not only for the wielder of the katana, but also for the sword smith and his creation.

The samurai sword, it is said, was believed to contain the soul of the warrior who owned it. While this is probably an over romanticised view, it is true to say that there was a spiritual connection not only for the wielder of the katana, but also for the sword smith and his creation.

The Muromachi Period

The Muromachi Period was a time of turmoil in Japan that can be spilt into two separate eras. At the beginning of the period, the government was divided into two separate entities sparking the Northern and Southern Courts Era. Then, after a brief period of relative stability, the Warring States Era began.

Tsukahara Bokuden

Tsukahara Bokuden was a samurai warrior who lived in the 16th century. In his early days he exemplified what a samurai should be and was known as one of the fiercest warriors around. However in later life, Bokuden would take on a more pacifist philosophical stand point.

Tsukahara Bokuden was a samurai warrior who lived in the 16th century. In his early days he exemplified what a samurai should be and was known as one of the fiercest warriors around. However in later life, Bokuden would take on a more pacifist philosophical stand point.

The Death of a

Samurai

The manner in which a samurai died was very important and if possible, it would be during combat in a way that would be told in samurai stories for years to come. Failing that, he should die in some other service to his lord or if his honour depended on it, in a ritualistic suicide known as seppuku.

The manner in which a samurai died was very important and if possible, it would be during combat in a way that would be told in samurai stories for years to come. Failing that, he should die in some other service to his lord or if his honour depended on it, in a ritualistic suicide known as seppuku.

The Duels of Miyamoto

Musashi

Miyamoto Musashi is

one of the most acclaimed samurai that ever lived. While undertaking a warrior’s pilgrimage,

he fought in over 60 duels dispatching the best swordsmen in a given area, often in fights to

the death.

The Samurai at War

The main business of the samurai was war and while tactics and weapons changed through the years, the willingness to die for their lord was a constant. In return, they could gain riches and status, as well as the best of them gaining a kind of immortality by having stories told about them for centuries to come.

The main business of the samurai was war and while tactics and weapons changed through the years, the willingness to die for their lord was a constant. In return, they could gain riches and status, as well as the best of them gaining a kind of immortality by having stories told about them for centuries to come.

The images on this site are believed to be in the public domain, however, if any mistakes have been made and your copyright or intellectual rights have been breeched, please contact andrew@articlesonhistory.com.

.jpg?timestamp=1583497671309)

thumb.jpg?timestamp=1583498733392)