The Muromachi Period

Talk the Talk

The Muromachi Period is named after the district in Heian-Kyo (modern-day Kyoto) where the bakufu (a feudal military government who were headed by

the shogun) were based.

The period is also known as the Ashikaga Period after the clan name of the shoguns of the era, starting with Takauji Ashikaga, who became

shogun in 1338.

Walk the Walk

In 1543, the very first Europeans to visit Japan arrived when a group of three Portuguese traders were blown ashore by a storm.

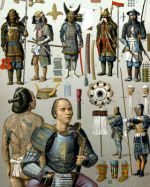

The new arrivals would introduce firearms to the samurai for the first time, which would soon be incorporated into their armies.

Some samurai leaders refused to use the new

weapons, considering them to have little honour as they took relatively little training to be used effectively.

However, those who embraced them tended to win more battles

because of the advantages their use provided.

They would go on to be instrumental in the army of Nobunaga Oda, whose tactical use of firearms helped him unify Japan

at the end of the period.

Samurai History Fact

Christianity was introduced to the Japanese for the first time during the Muromachi Period.

The concept was first introduced by the Portuguese traders

blown ashore in 1543 and the Jesuit Priest Francis Xavier would undertake a mission to the capital Heian-Kyo soon after in 1549 – 1550.

Many of the warlords embraced the new religion in a bid to increase trade with Europeans from whom they were keen to acquire military-related equipment and knowledge.

The Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573), also known as the Ashikaga Period, corresponds to the rule of the Ashikaga shogunate, starting when Takauji Ashikaga (pictured right) seized control of Japan in 1336 and ending with the exile of his descendant, Yoshiaki Ashikaga in 1573.

The Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573), also known as the Ashikaga Period, corresponds to the rule of the Ashikaga shogunate, starting when Takauji Ashikaga (pictured right) seized control of Japan in 1336 and ending with the exile of his descendant, Yoshiaki Ashikaga in 1573. The period started at the end of the Kemmu Restoration (1333 – 1336) after Emperor Go-Daigo’s attempt to bring Imperial rule back to Japan failed. Go-Daigo had managed to wrestle control from the bakufu (the military government headed by the shogun) with the help of Takauji.

However, when Takauji was refused the title of shogun after their victory, he turned on the emperor capturing the capital city Heian-Kyo in July 1336 and taking control of the country for himself.

The most important developments during the period came in two separate eras. The first spanned from 1336 – 1392 and is known as the Nanbokucho Period (the Northern and Southern Courts Era) and the second was from 1467 – 1573 and is called the Sengoku Period (the Warring States Era).

The Northern and Southern Courts Era

Two years after seizing control of Japan, Takauji Ashikaga named himself shogun. A new emperor, Komyo, was named and would act as a figurehead, a task made easier due to a succession dispute that had been going on since the death of Emperor Go-Saga in 1272.

Go-Daigo meanwhile fled to Yoshino ninety-five km (sixty miles) south of Heian-Kyo where he founded the Southern Imperial Court and continued to call himself Emperor.

This started the Northern and Southern Courts Era, also known as the Dual Courts Period, which saw the two opposing forces fight many battles with each other.

Takauji and his successors were generally in a more advantageous position as their armies were stronger. However, the Southern Court did manage to gain the upper hand several times by taking

control of the capital city, though they could only hold it for short periods of time and would soon lose out to the stronger Northern

forces.

When Go-Daigo died in 1339, the

government he founded was seriously weakened though did see a revival in strength soon after as a result of internal feuding within the Northern Court that lead to some daimyo

(military leaders who governed the provinces) switching their allegiances. This allowed the Southern Court to continue to exist for a while, but in 1392 during the reign of the third Ashikaga shogun,

Yoshimitsu, the two courts unified and the Southern Court was absorbed. Despite this, Emperors that belonged to the Northern

line are today considered by most historians as illegitimate and are not included in the official Imperial succession.

In spite of the upheaval caused by having two rival powers during the Nanbokucho Period, the country saw economic

growth in the early years of the Muromachi Period, in particular during the shogunate of Yoshimitsu who gained the title in 1368 at the age of ten. He significantly increased trade relations with China,

joining the Chinese Ming Dynasty’s tribute system from 1401. Ming goods such as porcelain, silk and bronze coins were popular imports to Japan while finely crafted

swords, copper ore and timber were often exported to China.

He also introduced new inheritance laws, applied tolls to roads and improvements in agriculture greatly increased food production.

With these changes came the development of new industries, new markets, a growing number of towns and even new social classes.

The Rise of the Daimyo

The sudden death of Yoshimitsu in 1408 saw the position of shogun weakened as the most powerful daimyo would soon begin to assert their

power. Peasant uprisings and an attempt to restore the Southern Court put pressure on the bakufu but at first, many of the daimyo attempted to consolidate the position of the shogun and his

government as it was this institution that supported their own dominance over their territories.

As a result the new shogun, Yoshinori Ashikaga, was able to crush a rebellion by Mochiuji Ashikaga and defeated the remnants of his forces in the Yuki War with the help of the provincial warlords. This meant there was nobody left to challenge the bakufu openly and seemed to restore stability to the country. However, Yoshinori ruled with an iron fist which led to the Kakitsu Rebellion and his assassination at the hands of Mitsusuke Akamatsu in 1441. From this point, a series of young boys held the position of shogun with a council of powerful daimyo running the country in their name.

On paper, the shogun and his bakufu were still ruling Japan however the daimyo had virtual autonomy over their own domains complete with standing armies that had no other loyalty but to them. Tax collection from the more powerful daimyo became impossible for the bakufu and political and cultural control of the country was therefore divided between several, often opposing, forces.

The Warring States Era

The Warring States Era, also known as the Age of the Country at War, began with the Onin War (1467 – 1477) which was initially fought over the rivalry of two clans, the Hosokawa and the Yamana. Even though the shogun held little power by this time, the two sides began fighting over who should hold the position and perhaps more importantly, who should be regent to the young shogun.

The conflict quickly escalated and would soon involve most of the powerful families of Japan, with clan leaders pledging their allegiance to one side or the other. With none of the forces able to assert themselves completely, the Onin War ended without a conclusive victory for either side. The capital city was in ruins and despite the war ending, fighting continued in rural areas. Many wars and insurrections would take place over the next century as warlords fought it out with each other for dominance but none of them were strong enough to actually gain control of the country for themselves.

What’s more, the fact that any power the shogun had was gone by the time of the Sengoku Period had a knock-on effect on many of the daimyo as respect for authority diminished. Many leading warlords were overthrown from their position as governors of their territories by their subordinates, others lost their power to peasant uprisings and others still saw religious orders rise up to challenge them.

As a result of the ongoing conflicts, castles were built more frequently than in any previous period. Towns, mountain passes and the estates of leading samurai warriors were fortified and new towns would often spring up around these strongholds. The castles would be built on a large stone base but would mostly be constructed of wood. They would consist of walls, towers and gates with narrow windows which were ideal for shooting arrows through; they would also have boulders hanging from ropes, ready to drop on any would-be attackers attempting to scale the walls.

Nobunaga Oda

By the middle of the sixteenth century, a small number of very powerful daimyo had risen and were competing for control of the country. The most powerful of these to emerge was Nobunaga Oda, who had been expanding his territories from his base, Nagoya Castle (pictured below), by defeating rival clans in battle.

Nobunaga supported the claim of Yoshiaki Ashikaga to be shogun and together they took control of the capital Heian-Kyo in 1568. However, philosophical and political differences would soon separate the two as Yoshiaki wanted to restore the old system, whereby the country would be run by the hereditary shogun and his bakufu.

Nobunaga however had his own ideas and his philosophy centred around the motto; Tenka Fubu (warriors rule all under heaven). Matters came to a head in 1573 when Yoshiaki was driven out of the capital bringing an end to the Muromachi Period and the reign of the Ashikaga shoguns. The bakufu system was dismantled at this point and a new form of government was created with Nobunaga, the most powerful warlord, as its leader.

Written by Andrew Griffiths – Last updated 20/07/2023. If you like

what you see, consider following the History of Fighting on social media.

Further Reading:

Ashikaga Period (1336 – 1568). [Internet]. 2019. The University of Pittsburgh. Available From:

https://www.japanpitt.pitt.edu/timeline/ashikaga-period-1336-1568 [Accessed Aug 29, 2019].

Mark Cartwright. [Internet]. 2019. Muromachi Period. Ancient History Encyclopaedia. Available From: https://www.ancient.eu/Muromachi_Period [Accessed Aug 29, 2019].

Muromachi Period (1333 - 1573). [Internet]. 2019. Japan-Guide.com. Available From:

https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2134.html [Accessed Aug 29, 2019].

Muromachi Period (1392–1573). [Internet]. 2002. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available From: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/muro/hd_muro.htm [Accessed Aug 29, 2019].

More Samurai History

Samurai History Home

A brief overview of the history of the samurai, looking at the rise and development of the leading social class in Japan and some of the cultural traits than made the samurai warriors unique such as their weapons and their code of ethics, known as bushido.

A brief overview of the history of the samurai, looking at the rise and development of the leading social class in Japan and some of the cultural traits than made the samurai warriors unique such as their weapons and their code of ethics, known as bushido.

The Heian

Period

The Heian Period was a time of major change in Japan as it saw the rise of a new warrior elite, the Samurai. The leaders of this new power would dominate the politics of the country for centuries and would even supplant the power of the Emperor, though not without a struggle.

The Heian Period was a time of major change in Japan as it saw the rise of a new warrior elite, the Samurai. The leaders of this new power would dominate the politics of the country for centuries and would even supplant the power of the Emperor, though not without a struggle.

Tomoe Gozen – Female Samurai Warrior

Tomoe Gozen is a rare example of a female Samurai warrior and is believed to have been involved in the Gempei wars (1180 – 1185). She fought alongside her Master, Minamoto Yoshinaka, though it is unclear how much of her story is actually true.

Tomoe Gozen is a rare example of a female Samurai warrior and is believed to have been involved in the Gempei wars (1180 – 1185). She fought alongside her Master, Minamoto Yoshinaka, though it is unclear how much of her story is actually true.

Yoshitsune Minamoto

The tragic tale of samurai legend Yoshitsune Minamoto. After helping his brother Yoritomo win the Genpei War and gain control of Japan, he was denied the titles and rewards he should have received for his services and was ultimately hunted down as a traitor.

The tragic tale of samurai legend Yoshitsune Minamoto. After helping his brother Yoritomo win the Genpei War and gain control of Japan, he was denied the titles and rewards he should have received for his services and was ultimately hunted down as a traitor.

The Kamakura Period

A look at the change and turmoil experienced by the ruling elite of Japan during the Kamakura Period and the Kemmu Restoration. A series of civil wars and two invasions from the Mongols saw powershifts not only between rival families, but also between the titles of the Emperor, the Shogun and the Regent.

A look at the change and turmoil experienced by the ruling elite of Japan during the Kamakura Period and the Kemmu Restoration. A series of civil wars and two invasions from the Mongols saw powershifts not only between rival families, but also between the titles of the Emperor, the Shogun and the Regent.

The Mongols vs. The Samurai

While the samurai warriors of the late thirteenth century were formidable warriors in their own right, when faced with the onslaught of the Mongol Hordes they seemed to be fated to lose. They were outclassed in every way by however things did not go according to plan for the foreign invaders.

While the samurai warriors of the late thirteenth century were formidable warriors in their own right, when faced with the onslaught of the Mongol Hordes they seemed to be fated to lose. They were outclassed in every way by however things did not go according to plan for the foreign invaders.

The Japanese Samurai Sword

The samurai sword, it is said, was believed to contain the soul of the warrior who owned it. While this is probably an over romanticised view, it is true to say that there was a spiritual connection not only for the wielder of the katana, but also for the sword smith and his creation.

The samurai sword, it is said, was believed to contain the soul of the warrior who owned it. While this is probably an over romanticised view, it is true to say that there was a spiritual connection not only for the wielder of the katana, but also for the sword smith and his creation.

Tsukahara Bokuden

Tsukahara Bokuden was a samurai warrior who lived in the 16th century. In his early days he exemplified what a samurai should be and was known as one of the fiercest warriors around. However in later life, Bokuden would take on a more pacifist philosophical stand point.

Tsukahara Bokuden was a samurai warrior who lived in the 16th century. In his early days he exemplified what a samurai should be and was known as one of the fiercest warriors around. However in later life, Bokuden would take on a more pacifist philosophical stand point.

The Death of a Samurai

The manner in which a samurai died was very important and if possible, it would be during combat in a way that would be told in samurai stories for years to come. Failing that, he should die in some other service to his lord or if his honour depended on it, in a ritualistic suicide known as seppuku.

The manner in which a samurai died was very important and if possible, it would be during combat in a way that would be told in samurai stories for years to come. Failing that, he should die in some other service to his lord or if his honour depended on it, in a ritualistic suicide known as seppuku.

The Duels of Miyamoto Musashi

Miyamoto Musashi is one of the most acclaimed samurai that ever lived. While undertaking a warrior’s pilgrimage, he fought in over 60 duels dispatching the best swordsmen in a given area, often in fights to the death.

The Samurai at War

The main business of the samurai was war and while tactics and weapons changed through the years, the willingness to die for their lord was a constant. In return, they could gain riches and status, as well as the best of them gaining a kind of immortality by having stories told about them for centuries to come.

The main business of the samurai was war and while tactics and weapons changed through the years, the willingness to die for their lord was a constant. In return, they could gain riches and status, as well as the best of them gaining a kind of immortality by having stories told about them for centuries to come.

The images on this site are believed to be in the public domain, however, if any mistakes have been made and your copyright or intellectual rights have been breeched, please contact andrew@articlesonhistory.com.

.jpg?timestamp=1581603988914)

thumb.jpg?timestamp=1581604699883)